Trees Planted To Reduce Erosion, Stabilize Streambank

Silky dogwood, buttonbush and elderberry were the most successful species in a recent live stake study conducted by Susquehanna University and the Chesapeake Conservancy.

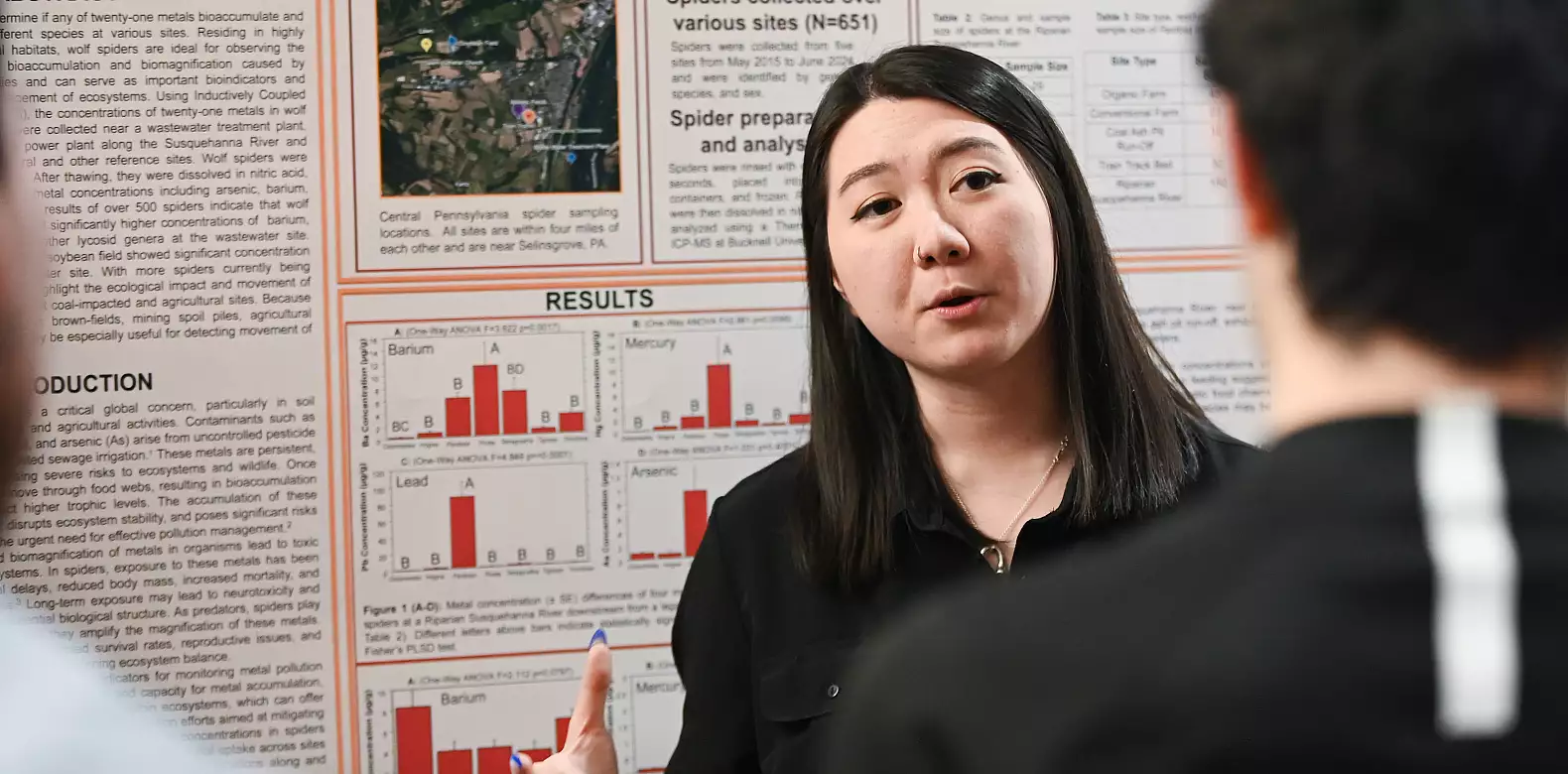

Matt Wilson, director of Susquehanna’s Freshwater Research InstituteAll three exhibited over a 45% survival rate, which is pretty good considering you are simply sticking a stake in the ground and leaving it alone to sprout and grow,” said Matt Wilson, director of Susquehanna’s Freshwater Research Institute. “None of the other species we studied had better than a 10% survival rate.”

Live stakes are cuttings off certain trees and shrubs that can be planted directly into the ground and can be very helpful in protecting local streams.

“We cut the branches off in the winter when the plant is dormant and then in the springtime when the ground is soft enough, we just stick the branch into the soil next to a stream,” said Shannon Thomas, live stake coordinator for the Chesapeake Conservancy. “Because the branch has stem cells in it, even though it is just a branch, we can put it into the ground, and it is able to grow roots and buds and leaves. Essentially from one piece of branch, it can grow into its own successful tree or shrub.”

Thomas, along with 3 other staff members from the conservancy work with Susquehanna out of the Freshwater Research Institute. The FRI and the Chesapeake Conservancy partner closely on watershed research, monitoring and restoration projects in central Pennsylvania. The conservancy works to determine where to implement streamside restoration for the greatest water quality improvement and lowest cost while the FRI samples these sites before and after restoration to understand the benefits. Additionally, SU students have given over 1,000 volunteer hours in support of conservancy-led restoration projects and conservancy staff have mentored over 20 Susquehanna students in internships.

Plenty of Perks

Live stake plantings provide a wide variety of benefits along our waterways, including streambank stabilization.

“The first instinct of the stake is to grow roots quickly and establish itself, and those roots can be very helpful in holding together streambanks and things like erosion and sediment pollution are reduced,” Thomas said. “What is unique with live stakes versus more traditional planting is that it doesn’t require a big hole or a flat surface. In places where streambanks are already eroding, live stakes can be inserted directly on an angle into the soil. Those roots will establish themselves and work quickly to improve the bank.”

Live stake plantings can also impact stream temperatures.

“It helps keep the temperature down as the canopy creates shade. Lower water temperatures are great for our trout populations,” Thomas said. “Also, the leaf litter that comes off the trees can be great food for macroinvertebrates that are living in the stream, so there are all sorts of fantastic benefits.”

Statistical Successes

In fall 2019 as Adrienne Gemberling was developing the Chesapeake Conservancy’s pilot of the live staking program in the region, Wilson partnered with her to develop a study to improve success of the program.

They gridded out 1.5 acres next to the stream, planting rows of eight different species that are commonly used for live staking efforts: silky dogwood, buttonbush, elderberry, winterberry holly, gray dogwood, speckled alder, spicebush and red osier dogwood.

The trees were treated four different ways — an herbicide treatment to keep down invasives, a rooting hormone, both a rooting hormone and an herbicide treatment and nothing.

“We wanted to determine what works and where money should be invested to make sure these projects are successful,” Wilson said.

They found that the rooting hormone and herbicide, for the most part, “didn’t help a whole lot.

“In certain circumstances, they did, like the silky dogwood did a little better with those agents, but none of the other species really did. In fact, some did worse with the rooting hormone,” said Wilson. “We went into it assuming better protection meant better chances for survival, which makes sense, but it really wasn’t the case for this.”

They also determined the superiority of silky dogwood, buttonbush and elderberry in terms of live staking success.

“The summer of the study was a very hot summer and probably as stressful as you’d encounter for these sorts of projects,” Wilson said. “Some of the other species may have done better if things were wetter, but if you want to hedge your bets, these three species seem to survive the best overall.”

Data from studies such as this are vital for live stake efforts, Thomas said.

“As I am out there running live stake collections, volunteers are always super interested in knowing how live staking works, what the success rates are and if it is worth the work we put into it,” she said. “It is really great to have real info and data to be able to answer those questions and let partners know that stakes will grow where we are putting them.”

The Chesapeake Conservancy’s live stake program, based out of Susquehanna University, serves a six-county region that includes Snyder, Union, Lycoming, Centre, Clinton and Huntingdon counties. For more information, visit the Chesapeake Conservancy’s website.

Story republished with permission from the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association.